The article appears below, here is a link to the original printed version.

Youngstown Business Journal Pine Knoll Clock Shop

One correction; my street number is 1749 Mercer Grove City Road.

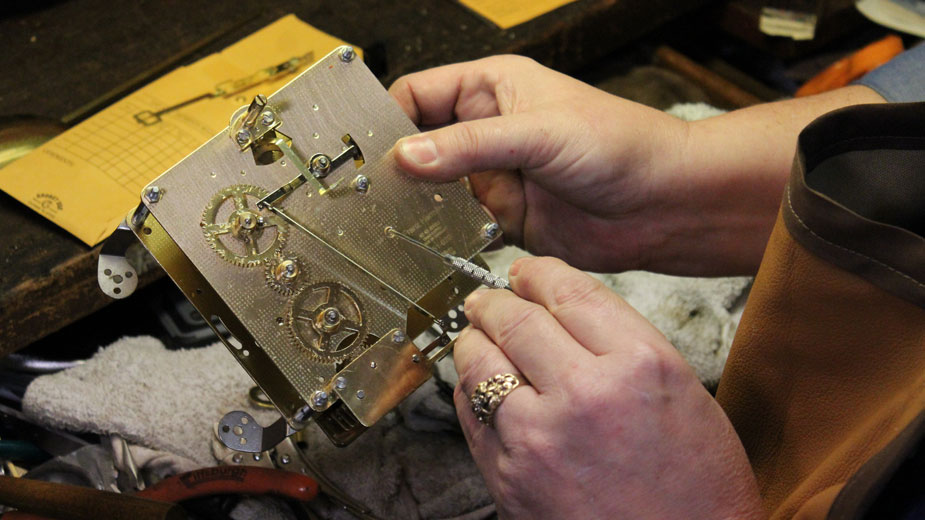

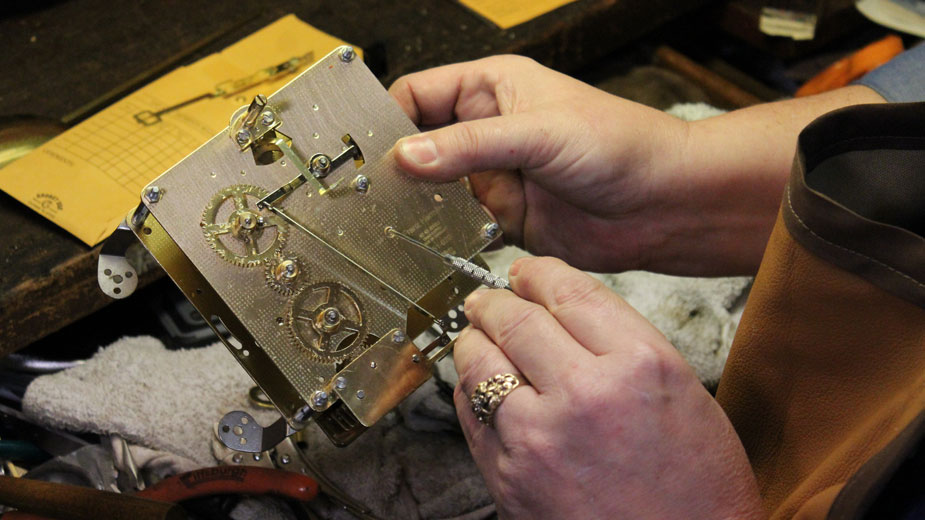

Dorrin Mace uses dental picks to clean out oil buildup on clocks.

Dorrin Mace uses dental picks to clean out oil buildup on clocks.

Youngstown Business Journal Pine Knoll Clock Shop

One correction; my street number is 1749 Mercer Grove City Road.

Company News

Work Keeps Ticking Along at Pine Knoll Clock Shop

MERCER, Pa. – For

horologist Dorrin Mace, an interest in clocks stretches back to the

Revolutionary War. His personal story starts a little closer to today,

but the items that caught his attention go back to the founding of the

nation.

“In 1969, my grandfather

died. They had a house that was granted to them after the Revolutionary

War, so about 1780. They never threw anything away and one of the summer

kitchens was full of every clock that house ever had,” Mace says from

his workshop. “I was just fascinated. I wasn’t very old, but I was

fascinated enough to know that’s what I wanted to do.”

Today, 50 years later, that fascination has grown into Pine Knoll Clock Shop, 1479 Mercer Grove City Road in Mercer, Pa.

Inside his workshop, Mace

repairs and refurbishes clocks of all ages, styles and conditions. In

one corner is a red and white Coca-Cola clock from the 1980s, while a

piece made in France in the mid-1800s sits on a cabinet across the room.

Leaning against the cabinet is one of Mace’s rarest finds to date: a

McClintock master clock. The clocks were once used by banks and

courthouses to control individual clocks throughout their offices via

electrical pulses that went off every minute.

“It played four different

melodies so you knew exactly what time it was. Instead of playing four

parts of a melody, this one had four distinct melodies. It played off a

drum over electric pickups to the main clock,” he says.

What makes the find so

exceptional isn’t its condition – most of the clock is “in a million

pieces in a bag” – but that it’s just one of three Mace knows to still

exist. Used largely in the 1920s and 1930s, the McClintock master clocks

were between 12 and 15 feet tall with large amounts of brass and

copper. When the United States entered World War II, many were scrapped

to aid the war effort.

“I don’t know how this one

survived, but I know there are three of these and none of them work. I’m

more than excited to have this,” Mace says of the clock he found in a

California junkyard. “I don’t know the value on this and it doesn’t

really matter.”

In his eyes, all clocks are

equally valuable. He’s worked on pieces with just a $10 price tag and

pieces designed by L.C. Tiffany. Just as much care is given to the $10

clock brought in by a boy who received it as a gift from his grandfather

as is given to the one designed by the man best known for stained-glass

works for Tiffany & Co.

“It may be a $10 clock, but to him it means everything,” Mace says.

Among the larger projects Mace has had is a clock weighing

about 700 pounds from Bultman Funeral Home in New Orleans, the oldest

funeral home in the city before it was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Mace purchased the clock from another clock repairman based in Michigan

and brought back into working condition. He estimated that had the work

been done for a customer, it would have been a $10,000 repair.

Today, it sits outside Pine Knoll.

Mace started repairing

clocks as a hobby, eventually offering help to others when he was about

18. As the years went on, it turned into a side job before coming into

its own as Pine Knoll Clock Shop in 2001.

“I started in the basement

and then the basement took over the dining room, which took over the

living room. It was overwhelming and we bought our first building,

thinking I’d work 20, 30 hours a week,” Mace says. “I was at a year and a

half wait on repairs, which you shouldn’t do. That really said to me

it’s time to leave [my other job].”

Today, his backlog is

usually around 12 weeks, with the time largely depending on the degree

of repairs needed – small adjustments can be done in his workshop – and

the availability of parts. When Mace started working on clocks, he says,

there were 15 parts suppliers, down to just two today, which can make

sourcing replacement parts a challenge.

“I have a huge group of

people that follow me – our blog has about 200,000 followers – that

include repairmen in Israel, South Africa and around the world that I

can contact,” he says. “There are some things that you can’t quote, that

you have say ‘I’ll call you back when I find the part.’ But cleaning,

oiling, adjusting suspensions, we know how long it takes to do that.”

In his arsenal of tools,

little is specific to clocks, he says. Among the ones he uses most often

are Phillips head screwdrivers – about a dozen because of the wide

variety of screws used in clocks over the past couple centuries – and

dental picks. One of his more prized tools is a set of carbide bits made

in France in the late 1800s.

“You use them as files to clean out pivots. They’re great in small areas,” he says. “Nothing here is a high-end tool.”

Dorrin Mace uses dental picks to clean out oil buildup on clocks.

Dorrin Mace uses dental picks to clean out oil buildup on clocks.

After repairs are made, he

lets clocks run for up to a week to ensure that there aren’t any more

problems with it and that everything is running smoothly.

Beyond fixing clocks, Mace

has also gotten into selling them. The front portion of Pine Knoll Clock

Shop is full to the brim of pieces repaired or built by Mace, ranging

from cuckoo clocks to towering grandfather clocks. There’s also the

Green Line, developed by Mace as a way to recycle discarded materials.

“I saw so much waste. My

wife and I are hippies, for lack of a better term,” he says with a

laugh. “We saw flooring that couldn’t be used and had some worn damage

but once it’s sanded, it’s just gorgeous. Fencing that’s been damaged by

weather can be beautiful. You’re saving resources.”

He’s turned old records

into timepieces, as well as hubcaps, pieces of tin ceilings and, at one

point, even gears from Harley Davidson motorcycles.

And even with the

increasing use of smartphones and watches, Mace says business is as good

as ever. His clientele stretches across generations as younger people,

he observes, fall in love with one particular aspect of clocks.

“It’s the sound of a clock

ticking. There used to be an advertising slogan: ‘The heartbeat of the

home.’ People are remembering that,” he says. “It’s like reading a book.

Having an e-reader is fine, but there’s the tactile feel of the book.

Watching the hands ticking is just phenomenal.

Pictured: Dorrin Mace, owner of Pine Knoll Clock Shop, with his McClintock master clock, one of three he knows to exist.

Copyright 2019 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.